Displaced Nigerians Face Starvation in Maiduguri

MAIDUGURI, NIGERIA —

The food shortage gripping northeast Nigeria is most obvious on the streets of the Borno State capital, Maiduguri. Long lines meander along the sidewalks as people wait for handouts from charities. Sometimes, the people in line become unruly.

“I will beat you!” shouts a crowd control officer to a slender woman in an orange hijab. She had rushed to the front of a line where workers from the World Food Program were giving away one-month supplies of baby food.

Women wait for free baby food donations from the U.N.'s World Food Program in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Women wait for free baby food donations from the U.N.'s World Food Program in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

The woman is just one of millions of people who are feeling the pinch of unprecedented food insecurity in northeastern Nigeria.

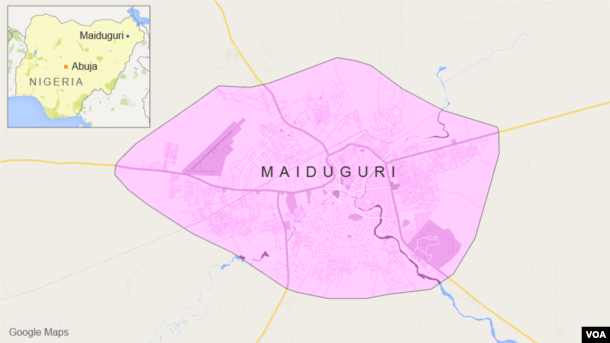

For seven years, Boko Haram militants have been at war with the Nigerian government. Sect members have targeted civilians — destroying farmland and stealing livestock. Families have fled to the cities, especially Maiduguri, which is now housing more than a million displaced people.

Maiduguri, Nigeria

Maiduguri, Nigeria

Hunger and widespread malnutrition are the result.

“Today in Maiduguri, malnutrition is way above 20 percent,” says Dr. Jarvid Ali, the emergency medical coordinator of Doctors Without Borders’ activities in Borno State. “That means in terms of the gravity of the situation, the magnitude of severe acute malnutrition, it’s really huge.”

Many people cannot afford to buy food and some displaced people say the rations in the refugee camps are not enough.

Widespread malnutrition affects thousands of children in northeastern Nigeria, where Boko Haram violence has disrupted farming and trade, in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Widespread malnutrition affects thousands of children in northeastern Nigeria, where Boko Haram violence has disrupted farming and trade, in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Inusa Isa lives at the NYSC camp in Maiduguri. He says he has not eaten a solid meal in the past five days.

“Up 'til now, the government did not bring food for us for 42 days. So today we will eat food; tomorrow we will not eat food. We usually don’t eat food for days,” Isa says. "We are dying of hunger. Shortly after I came here, my wife died. We just lost a baby three days ago that my brother’s wife gave birth to. My brother is dead. My father died not too long ago.”

Isa says he sometimes resorts to begging for money and the little money that he is able to get, he often uses to buy medication or to pay for funerals for his relatives.

The food insecurity has reached famine levels and Maiduguri residents say they have noticed a rise in the number of deaths.

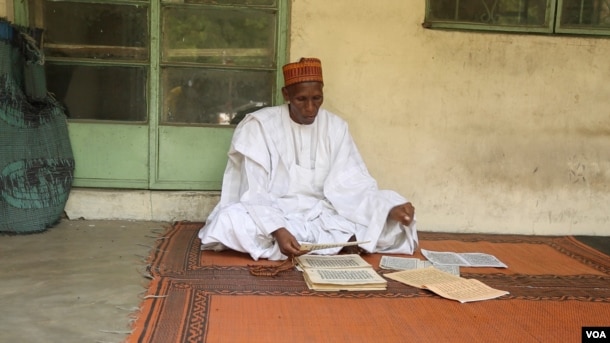

In the past few months alone, Mallam Goni has had to attend more funerals than ever before in his 30-year career as a preacher.

Mallam Goni says he has attended more funerals in the past few months that ever in his 30-year career as an Islamic preacher in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Mallam Goni says he has attended more funerals in the past few months that ever in his 30-year career as an Islamic preacher in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

“Before, we were not supposed to pray for dead people because we delegate that to the head mallam; but, these days, the deaths are so common. You’ll be talking to someone and then before you know it, they will say their relative died of hunger. So we just have to go to the funerals to pray. The deaths are just too many to count,” Goni says.

Most of the corpses go to the Gwange Cemetery, the largest in the city. Attendants there say they are struggling to find spaces to dig new graves.

“The graveyard is full. We keep digging graves every day. It wasn’t like this a few months ago. And if you check, it’s mostly these IDP's [internally displaced persons] who are just dying of hunger,” says Baba Gana Modu.

The mortality rate at the health clinics is also alarming. Dr. Ali said in August, 72 people died in one of their facilities where they treat the most severe cases of malnutrition.

The International Rescue Committee opened a clinic at a local hospital in September.

“When we first started at opening, we saw one or two kids die a night,” says Carmen Yip, IRC’s emergency medical coordinator.

IRC pushed a community campaign last month to encourage families to bring in their children to the hospital earlier. Yip says this drastically reduced the death rate.

Every day, Doctors Without Borders sees about 1,000 people in its health facilities in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Every day, Doctors Without Borders sees about 1,000 people in its health facilities in Maiduguri, Nigeria, October 2016. (C. Oduah/VOA)

Even when families do come in, health workers face a challenge in communicating a child’s needs to the parents. They say parents may not understand some of the treatment protocol — for example, the need for the sick child to be placed on a three-hour feeding schedule.

Yahawa Abukaka brought her 2-year-old daughter, Maryam, into the IRC clinic a few days ago.

“She was very bad. She was not even walking and her hair was falling out,” Abukaka says, looking at her daughter. The daughter’s hair is dusty red, the telltale sign of vitamin deficiency.

The health workers started Maryam on a low-protein milk before feeding her with a peanut butter-based supplement. Abukaka says she began to show signs of improvement.

“She is responding very well now and I am happy,” she says.

They will soon be discharged.

The United Nations says about 184 children will die in northeastern Nigeria each day if they do not receive help.

Isa is struggling to ward off hunger so he can stay alive for his two remaining children. After days without food, he manages to get a drink — squeezed from hibiscus flowers — and a fried bread snack.

Tomorrow, he’ll search again for something to eat.

Share this post

Naijanetwork Forum Statistics

Threads: 14842,

Posts: 17901,

Members: 6711